Statistical Comparisons

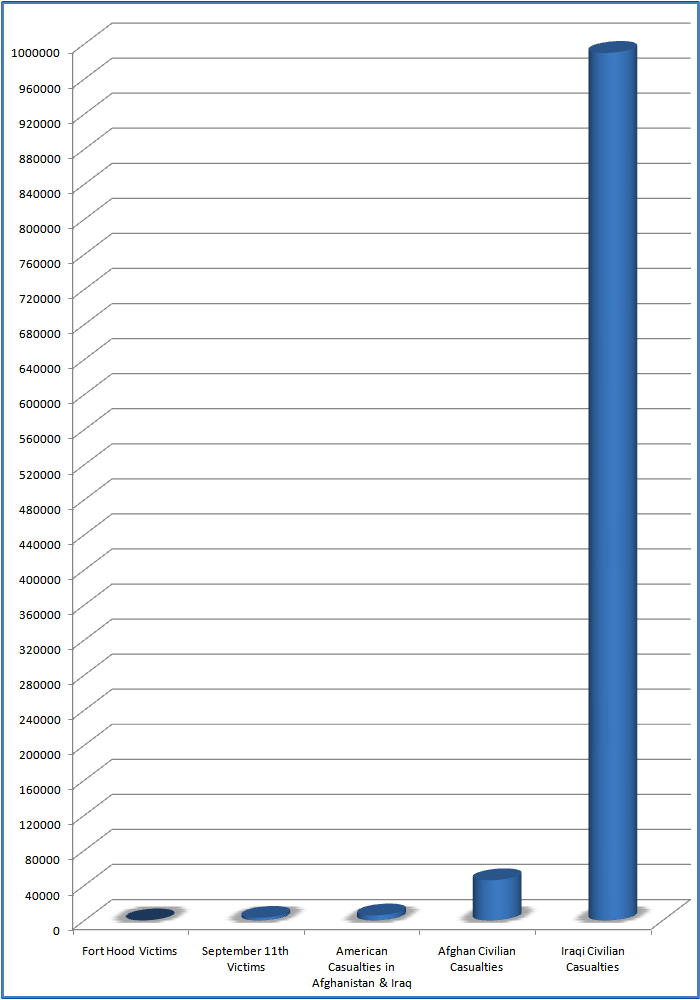

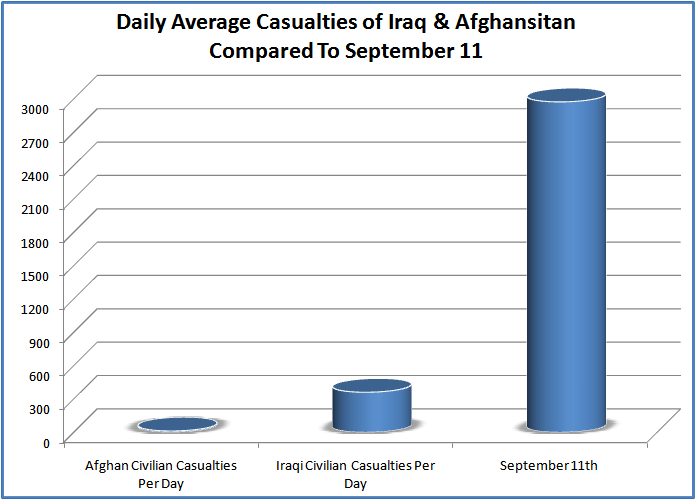

Iraq experiences 27.79 Fort Hood shootings a day and averages the equivalent casualties of September 11th every 8.23 days.

Afghanistan experiences 1 Fort Hood shooting a day and averages the equivalent casualties of September 11th every 231.24 days.

Iraq and Afghanistan combined experience 28.78 Fort Hood shootings a day and average the equivalent casualties of September 11th every 7.95 days.

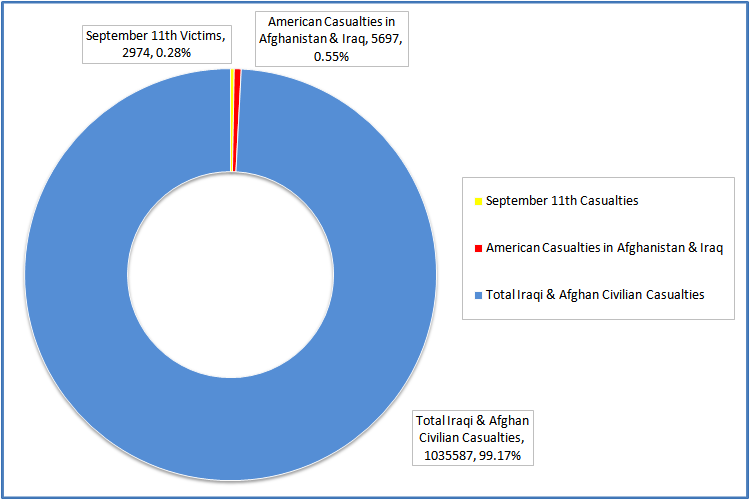

In total, Iraq and Afghanistan have experienced the equivalent of 348 September 11ths or 79960 Fort Hood shootings.

Methodology

Iraq Civilian Casualties: There is high variance between various sources on the number of civilian casualties since the US-led invasion in March 2003. The only source to calculate Iraqi civilian casualties since the invasion is Iraq Body Count, which only counts bodies confirmed by the Western media, leading it to severely under-report the total number of civilians killed since March 2003. Correspondingly, other studies only cover specific time periods. For instance, the most recognized study conducted by Lancet and John Hopkins University in October 2006 listed over 650,000 killed. Data is then extrapolated to represent the March 2003 to September 2010 timeframe.

Afghanistan Civilian Casualties: Currently, no study exists that comprehensively covers the total civilian casualties since the October 2001 aerial campaign and subsequent invasion. Most studies focus on yearly statistics or casualties deriving from a specific method (aerial bombing, improvised explosive devices, etc.). When possible, yearly computations were combined or extrapolated to find a total, as was done in the excellent table provided in Wikipedia’s page on civilian casualties since the US Invasion.

Base Statistics: September 11 Victims: 2,974; American Casualties in Afghanistan & Iraq: 5697; Afghan Civilian Casualties: 45,799; Iraqi Civilian Casualties: 989788′ Total Iraqi & Afghan Civilian Casualties: 1035587; Average Daily Civilian Casualties, Iraq & Afghanistan: 374.18. Click here to download the spreadsheet used to calculate the above numbers.

Sources on Iraq Casualties

Iraq Body Count, http://www.iraqbodycount.org

Casualties in Iraq: The Human Cost of Occupation, http://www.antiwar.com/casualties/

Bush’s War Totals by John Tirmar in the Nation http://www.thenation.com/doc/20090216/tirman

CNN: US & Coalition Casualties in Iraq http://www.cnn.com/SPECIALS/2003/iraq/forces/casualties/

Just Foreign Policy: Iraqi Death Estimates,

http://www.justforeignpolicy.org/iraq/iraqdeaths.html

http://www.justforeignpolicy.org/iraq/iraqdeaths.html

Wikipedia: Total Iraqi Casualties, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Casualties_of_the_Iraq_War#Total_Iraqi_casualties

Project Censored: Over One Million Iraqi Deaths Caused by US Occupation, http://www.projectcensored.org/top-stories/articles/1-over-one-million-iraqi-deaths-caused-by-us-occupation/

Sources on Afghanistan Casualties:

CNN: US & Coalition Casualties in Afghanistan, http://www.cnn.com/SPECIALS/2004/oef.casualties/index.html

Afghanistan Conflict Monitor: Civilian Casualty Data, http://www.afghanconflictmonitor.org/civilian.html,http://www.afghanconflictmonitor.org/civilian_casualties/index.html

A Dossier on Civilian Victims of United States’ Aerial Bombing of Afghanistan: A Comprehensive Accounting,http://cursor.org/stories/civilian_deaths.htm

Coalition Casualties in Afghanistan, http://icasualties.org/oef/

AFP: Afghan unrest killed 4,000 civilians in 2008,http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5jin59v7_ci05Cs9KtqexpO_1NxKA

Wikipedia Compilation Of Civilian Deaths in Afghanistan,http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Civilian_casualties_of_the_U.S._invasion_of_Afghanistan

Sources On Afghan & Iraqi Casualties

Unknown News: Casualties in Afghanistan and Iraq, http://www.unknownnews.net/casualties.html

The Star: Counting the casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan, http://www.thestar.com/columnists/article/259269

Previous Prose Before Hos reports on Iraqi & Afghan Casualties: Every 9.74 Days, Iraqi Civilians Experience September 11thand Civilian Death Statistics in Iraq & Afghanistan Compared.

Technorati Tags: september 11th, iraq civilian casualties, afghanistan civilian casualties, fort hood shootings, 9/11, war on terror, iraq invasion, invasion of afghanistan, iraqi civilians, afghani civilians, deaths, casualties, statistics, graphs, analysis,averages, totals, comparisons, george bush, barack obama, report and statistics on civilian deaths from us occupations, us military, middle east

Report claims just one in fifty victims of ‘surgical’ US strikes in Pakistan are known militants. Jerome Taylor reports on a deadly new strategy.

Late in the evening on 6 June this year an unmanned drone was flying high above the Pakistani village of Datta Khel in north Waziristan.

The buzz emitted by America’s fleet of Predators and Reapers are a familiar sound for the inhabitants of the dusty hamlet, which lies next to a riverbed close to Pakistan’s border with Afghanistan and is a stronghold for the Taliban commander Hafiz Gul Bahadur.

As the drone circled it let off the first of its Hellfire missiles, slamming into a small house and reducing it to rubble. When residents rushed to the scene of the attack to see if they could help they were struck again.

According to reports at the time, three local rescuers were killed by a second missile whilst a further strike killed another three people five minutes later. In all, somewhere between 17 and 24 people are thought to have been killed in the attack.

The Datta Khel assault was just one of the more than 345 strikes that have hit Pakistan’s tribal areas in the past eight years but it reveals an increasingly common tactic now being used in America’s covert drone wars – the “double-tap” strike.

More and more, while the overall frequency of strikes has fallen since a Nato attack in 2011 killed 24 Pakistani soldiers and strained US-Pakistan relations, initial strikes are now followed up by further missiles in a tactic which lawyers and campaigners say is killing an even greater number of civilians. The tactic has cast such a shadow of fear over strike zones that rescuers often wait for hours before daring to visit the scene of an attack.

“These strikes are becoming much more common,” Mirza Shahzad Akbar, a Pakistani lawyer who represents victims of drone strikes, told The Independent. “In the past it used to be a one-off, every now and then. Now almost every other attack is a double tap. There is no justification for it.”

The expansive use of “double-tap” drone strikes is just one of a number of more recent phenomena in the covert war run by the US against violent Islamists that has been documented in a new report by legal experts at Stanford and New York University.

The product of nine months’ research and more than 130 interviews, it is one of the most exhaustive attempts by academics to understand – and evaluate – Washington’s drone wars. And their verdict is damning.

Throughout the 146-page report, which is released today, the authors condemn drone strikes for their ineffectiveness.

Despite assurances the attacks are “surgical”, researchers found barely 2 per cent of their victims are known militants and that the idea that the strikes make the world a safer place for the US is “ambiguous at best.”

Researchers added that traumatic effects of the strikes go far beyond fatalities, psychologically battering a population which lives under the daily threat of annihilation from the air, and ruining the local economy.

They conclude by calling on Washington completely to reassess its drone-strike programme or risk alienating the very people they hope to win over. They also observe that the strikes set worrying precedents for extra-judicial killings at a time when many nations are building up their unmanned weapon arsenals.

The Obama administration is unlikely to heed their demands given the zeal with which America has expanded its drone programme over the past two years. Reapers and Predators are now active over the skies of Somalia and Yemen as well as Pakistan and – less covertly – Afghanistan.

But campaigners like Mr Akbar hope the Stanford/New York University research may start to make an impact on the American public.

“It’s an important piece of work,” he said. “No one in the US wants to listen to a Pakistani lawyer saying these strikes are wrong. But they might listen to American academics.”

Reprieve, the charity which is trying to challenge drone strikes in the British, Pakistani and American courts, said the report detailed how the fallout from the extra-judicial strikes must be measured in terms of more than deaths and injuries alone.

“An entire region is being terrorised by the constant threat of death from the skies,” said Reprieve’s director, Clive Stafford Smith.

“Their way of life is collapsing: kids are too terrified to go to school, adults are afraid to attend weddings, funerals, business meeting or anything that involves gathering in groups.”

Some of the most harrowing personal testimonies involve those who have witnessed “double-tap” strikes.

Researchers said people in Waziristan – the tribal area where most of the strikes take place – are “acutely aware of reports of the practice of follow-up strikes”, and explained that the secondary strikes have discouraged ordinary civilians from coming to one another’s rescue.

One interviewee, describing a strike on his in-laws’ home, said a follow-up missile killed would-be rescuers. “Other people came to check what had happened; they were looking for the children in the beds and then a second drone strike hit those people.”

A father of four, who lost one of his legs in a drone strike, admitted: “We and other people are so scared of drone attacks now that when there is a drone strike, for two or three hours nobody goes close to [the location of the strike]. We don’t know who [the victims] are, whether they are young or old, because we try to be safe.”

TESTIMONIES

“The villagers brought us the news.”

Khairullah Jan, whose brother was killed in a drone attack.

“I was … going to my house. That’s when I heard a drone strike and I felt something in my heart. I thought something had happened, but we didn’t get to know until the next day. That’s when all the villagers came and brought us news that [my brother] had been [killed]… I was drinking tea when I found out. [My] entire family was there.”

“My father’s body was scattered in pieces.”

Waleed Shiraz, who was studying for a BA before he was injured by a strike.

“My father was asleep … and I was studying near by … [When we got hit], [my] father’s body was scattered in pieces and he died immediately, but I was unconscious for three to four days … [Since then], I am disabled. My legs have become so weak and skinny that I am not able to walk.”

“Children, women, they are all affected.”

Firoz Ali Khan, a shopkeeper in the town of Miranshah.

“I have been seeing drones since the first one appeared about four to five years ago … [We see drones] hovering [24 hours a day but] we don’t know when they will strike … People are afraid of dying … Children, women, they are all psychologically affected. They look at the sky to see if there are drones… [They] make such a noise that everyone is scared.”

JEROME TAYLOR

SPEARHEAD RESEARCH

SPEARHEAD RESEARCH

The CIA’s programme of “targeted” drone killings in Pakistan’s tribal heartlands is politically counterproductive, kills large numbers of civilians and undermines respect for international law, according to a report by US academics.

The study by Stanford and New York universities’ law schools, based on interviews with victims, witnesses and experts, blames the US president, Barack Obama, for the escalation of “signature strikes” in which groups are selected merely through remote “pattern of life” analysis.

Families are afraid to attend weddings or funerals, it says, in case US ground operators guiding drones misinterpret them as gatherings of Taliban or al-Qaida militants.

“The dominant narrative about the use of drones in Pakistan is of a surgically precise and effective tool that makes the US safer by enabling ‘targeted killings’ of terrorists, with minimal downsides or collateral impacts. This narrative is false,” the report, entitled Living Under Drones, states.

The authors admit it is difficult to obtain accurate data on casualties “because of US efforts to shield the drone programme from democratic accountability, compounded by obstacles to independent investigation of strikes in North Waziristan”.

The “best available information”, they say, is that between 2,562 and 3,325 people have been killed in Pakistan between June 2004 and mid-September this year – of whom between 474 and 881 were civilians, including 176 children. The figures have been assembled by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, which estimated that a further 1,300 individuals were injured in drone strikes over that period.

The report was commissioned by and written with the help of the London-based Reprieve organisation, which is supporting action in the British courts by Noor Khan, a Pakistani whose father was killed by a US drone strike in March 2011. His legal challenge alleges the UK is complicit in US drone strikes because GCHQ, the eavesdropping agency, shares intelligence with the CIA on targets for drone strikes.

“US drones hover 24 hours a day over communities in north-west Pakistan, striking homes, vehicles, and public spaces without warning,” the American law schools report says.

“Their presence terrorises men, women, and children, giving rise to anxiety and psychological trauma among civilian communities. Those living under drones have to face the constant worry that a deadly strike may be fired at any moment, and the knowledge that they are powerless to protect themselves.

“These fears have affected behaviour. The US practice of striking one area multiple times, and evidence that it has killed rescuers, makes both community members and humanitarian workers afraid or unwilling to assist injured victims.”

The study goes on to say: “Publicly available evidence that the strikes have made the US safer overall is ambiguous at best … The number of ‘high-level’ militants killed as a percentage of total casualties is extremely low – estimated at just 2% [of deaths]. Evidence suggests that US strikes have facilitated recruitment to violent non-state armed groups, and motivated further violent attacks … One major study shows that 74% of Pakistanis now consider the US an enemy.”

Coming from American lawyers rather than overseas human rights groups, the criticisms are likely to be more influential in US domestic debates over the legality of drone warfare.

“US targeted killings and drone strike practices undermine respect for the rule of law and international legal protections and may set dangerous precedents,” the report says, questioning whether Pakistan has given consent for the attacks.

“The US government’s failure to ensure basic transparency and accountability in its targeted killings policies, to provide details about its targeted killing programme, or adequately to set out the legal factors involved in decisions to strike hinders necessary democratic debate about a key aspect of US foreign and national security policy.

“US practices may also facilitate recourse to lethal force around the globe by establishing dangerous precedents for other governments. As drone manufacturers and officials successfully reduce export control barriers, and as more countries develop lethal drone technologies, these risks increase.”

The report supports the call by Ben Emmerson QC, the UN’s special rapporteur on countering terrorism, for independent investigations into deaths from drone strikes and demands the release of the US department of justice memorandums outlining the legal basis for US targeted killings in Pakistan.

The report highlights the switch from the former president George W Bush’s practice of targeting high-profile al-Qaida personalities to the reliance, under Obama’s administration, of analysing patterns of life on the ground to select targets.

“According to US authorities, these strikes target ‘groups of men who bear certain signatures, or defining characteristics associated with terrorist activity, but whose identities aren’t known’,” the report says. “Just what those ‘defining characteristics’ are has never been made public.” People in North Waziristan are now afraid to attend funerals or other gatherings, it suggests.

Fears that US agents pay informers to attach electronic tags to the homes of suspected militants in Pakistan haunt the tribal districts, according to the study. “[In] Waziristan … residents are gripped by rumours that paid CIA informants have been planting tiny silicon-chip homing devices that draw the drones.

“Many of the Waziris interviewed spoke of a constant fear of being tagged with a chip by a neighbour or someone else who works for either Pakistan or the US, and of the fear of being falsely accused of spying by local Taliban.”

Reprieve’s director, Clive Stafford Smith, said: “An entire region is being terrorised by the constant threat of death from the skies. Their way of life is collapsing: kids are too terrified to go to school, adults are afraid to attend weddings, funerals, business meetings, or anything that involves gathering in groups.

“George Bush wanted to create a global ‘war on terror’ without borders, but it has taken Obama’s drone war to achieve his dream.”

It’s pop-quiz time when it comes to the American way of war: three questions. Here’s the first of them, and good luck!

A few weeks ago, 200 US Marines began armed operations in…?:

a) Afghanistan

b) Pakistan

c) Iran

d) Somalia

e) Yemen

f) Central Africa

g) Northern Mali

h) The Philippines

i) Guatemala

b) Pakistan

c) Iran

d) Somalia

e) Yemen

f) Central Africa

g) Northern Mali

h) The Philippines

i) Guatemala

If you opted for any answer, “a” through “h”, you took a reasonable shot at it. After all, there’s an ongoing American war in Afghanistan and somewhere in the southern part of that country, 200 armed US Marines could well have been involved in an operation.

In Pakistan, an undeclared, CIA-run air war has long been under way, and in the past there have been armed border crossings by US special operations forces as well as US piloted cross-border air strikes, but no Marines.

When it comes to Iran, Washington’s regional preparations for war are staggering. The continual build-up of US naval power in the Persian Gulf, of land forces on bases around that country, of air power (and anti-missile defences) in the region should leave any observer breathless.

There are US special operations forces near the Iranian border and CIA drones regularly over that country. In conjunction with the Israelis, Washington has launched acyberwar against Iran’s nuclear programme and computer systems. It has also established fierce oil and bankingsanctions, and there seem to have been at least some UScross-border operations into Iran going back to at least 2007.

In addition, a recent front-page New York Times story on Obama administration attempts to mollify Israel over its Iran policy included this ominous line: “The administration is also considering… covert activities that have been previously considered and rejected”. So 200 armed Marines in action in Iran – not yet, but don’t get down on yourself, it was a good guess.

In Somalia, according to Wired magazine’s Danger Room blog, there have been far more US drone flights and strikes against the Islamic extremist al-Shabab movement and al-Qaeda elements than anyone previously knew.

In addition, the US has at least partially funded, supported, equipped, advised and promoted proxy wars there, involving Ethiopian troops back in 2007 and more recently Ugandan and Burundi troops (as well as an invading Kenyan army). In addition, CIA operatives and possibly other irregulars and hired guns are well established in Mogadishu, the capital.

In Yemen, as in Somalia, the combination has been proxy war and strikes by drones (as well as piloted planes), with some US special forces advisers on the ground, and civilian casualties (and anger at the US) rising in the southern part of the country – but also, as in Somalia, no Marines.

Central Africa? Now, there’s a thought. After all, at least 100 Green Berets were sent in there this year as part of a campaign against Joseph Kony’s Ugandan-based Lord’s Resistance Army.

As for Northern Mali, taken over by Islamic extremists (including an al-Qaeda-affiliated group), it certainly presents a target for future US intervention – and we still don’t know what those three US Army commandos who skidded off a bridge to their deaths in their Toyota Land Rover with three “Moroccan prostitutes” were doing in a country with which the US military had officially cut its ties after a democratically elected government was overthrown. But 200 Marines operating in war-torn areas of Africa? Not yet.

When it comes to the Philippines, again no Marines, even though US special forces and drones have been aiding the government in a low-level conflict with Islamic militants in Mindanao.

As it happens, the correct, if surprising, answer is “i”. And if you chose it, congratulations!

Force as first choice

On August 29, the Associated Press reported that a “team of 200 US Marines began patrolling Guatemala’s western coast this week in an unprecedented operation to beat drug traffickers in the Central America region, a US military spokesman said Wednesday.”

This could have been big news. It’s a sizeable enough intervention: 200 Marines sent into action in a country where we last had a military presence in 1978. If this wasn’t the beginning of something bigger and wider, it would be surprising, given that commando-style operatives from the US Drug Enforcement Administration have been firing weapons and killing locals in a similar effort in Honduras, and that, along with US drones, the CIA is evidently moving ever deeper into the drug war in Mexico.

In addition, there’s a history here. After all, in the early part of the previous century, sending in the Marines - in Nicaragua, Haiti, the Dominican Repubic and elsewhere – was the way Washington demonstrated its power in its own “backyard”.

And yet, other than a few straightforward news reports on the Guatemalan intervention, there has been no significant media discussion, no storm of criticism or commentary, no mention at either political convention, and no debate or discussion about the wisdom of such a step in this country. Odds are that you didn’t even notice that it had happened.

Think of it another way: in the post-2001 era, along with two disastrous wars on the Eurasian mainland, we’ve been regularly sending in the Marines or special operations forces, as well as naval, air and robotic power. Such acts are, by now, so ordinary that they are seldom considered worthy of much discussion here, even though no other country acts (or even has the capacity to act) this way. This is simply what Washington’s National Security Complex does for a living.

At the moment, it seems, a historical circle is being closed with the Marines once again heading back into Latin America as the “drug war” Washington proclaimed years ago becomes an actual drug war. It’s a demonstration that, these days, when Washington sees a problem anywhere on the planet, its version of a “foreign policy” is most likely to call on the US military. Force is increasingly not our option of last resort, but our first choice.

World’s sole arms dealer

Now, consider question two in our little snap quiz of recent war news:

In 2011, what percentage of the global arms market did the US control?

(Keep in mind that, as everyone knows, the world is an arms bazaar filled with haggling merchants. Though the Cold War and the superpower arms rivalry is long over, there are obviously plenty of countries eager to peddle their weaponry, no matter what conflicts may be stoked as a result.)

a) 37 per cent ($12.1bn), followed closely by Russia ($10.7bn), France, China and the United Kingdom.

b) 52.7 per cent ($21.3bn), followed by Russia at 19.3 per cent ($12.8bn), France, Britain, China, Germany and Italy.

c) 68 per cent ($37.8bn), followed by Italy at 9 per cent ($3.7bn) and Russia at 8 per cent ($3.5bn).

d) 78 per cent ($66.3bn), followed by Russia at 5.6 per cent ($4.8bn).

b) 52.7 per cent ($21.3bn), followed by Russia at 19.3 per cent ($12.8bn), France, Britain, China, Germany and Italy.

c) 68 per cent ($37.8bn), followed by Italy at 9 per cent ($3.7bn) and Russia at 8 per cent ($3.5bn).

d) 78 per cent ($66.3bn), followed by Russia at 5.6 per cent ($4.8bn).

Naturally, you naturally eliminated “d” first. Who wouldn’t? After all, cornering close to 80 per cent of the arms market would mean that the global weapons bazaar had essentially been converted into a monopoly operation.

Of course, it’s common knowledge that the US arms giants, given a massive helping hand in their marketing by the Pentagon, remain the collective 800-pound gorilla in any room. But 37 per cent of that market is nothing to sniff at. (At least, it wasn’t in 1990, the final days of the Cold War when the Russians were still a major competitor worldwide.)

As for 52.7 per cent, what national industry wouldn’t bask in the glory of such a figure – a majority share of arms sold worldwide? (And, in fact, that was an impressive percentage back in the dismal sales year of 2010, when arms budgets worldwide were still feeling the pain of the lingering global economic recession.)

Okay, so what about that hefty 68 per cent? It couldn’t have been a more striking achievement for US arms makers back in 2008 in what was otherwise distinctly a lagging market.

The correct answer for 2011, however, is the singularly unbelievable one: the US actually tripled its arms sales last year, hitting a record high, and cornering almost 78 per cent of the global arms trade. This was reported in lateAugust but, like those 200 Marines in Guatemala, never made onto front pages or into the top TV news stories.

And yet, if arms were drugs (and it’s possible that, in some sense, they are, and that we humans can indeed get addicted to them), then the US has become something close enough to the world’s sole dealer. That should be front-page news, shouldn’t it?

Long-range surveillance missions

Okay, so here’s the third question in today’s quiz:

From a local base in which country did US Global Hawk drones fly long-range surveillance missions between late 2001 and at least 2006?

a) The Seychelles Islands

b) Ethiopia

c) An unnamed Middle Eastern country

d) Australia

b) Ethiopia

c) An unnamed Middle Eastern country

d) Australia

Actually, the drone base the US has indeed operated in the Seychelles Islands in the Indian Ocean was first usedonly in 2009 and the drone base Washington has developed in Ethiopia by upgrading a civilian airport only became operational in 2011. As for that “unnamed Middle Eastern country“, perhaps Saudi Arabia, the new airstrip being built there, assumedly for the CIA’s drones, may now be operational.

Once again, the right answer turns out to be the unlikely one. Recently, the Australian media reported that the US had flown early, secretive Global Hawk missions out of a Royal Australian Base at Edinburg. These were detectedby a “group of Adelaide aviation historians”.

The Global Hawk, an enormous drone, can stay in the air a long time. What those flights were surveilling back then is unknown, though North Korea might be one guess. Whether they continued beyond 2006 is also unknown.

Unlike the previous two stories, this one never made it into the US media and if it had, would have gone unnoticed anyway. After all, who in Washington or among US reporters and pundits would have found it odd that, long before its recent, much-ballyhooed “pivot” to Asia, the US was flying some of its earliest drone missions over vast areas of the Pacific?

Who even finds it strange that, in the years since 2001, the US has been putting together an ever more elaborate network of its own drone bases on foreign soil, or that the US has an estimated 1,000-1,200 military bases scattered across the planet, some the size of small American towns (not to speak of scads of bases in the United States)?

Like those Marines in Guatemala, like the near-monopoly on the arms trade, this sort of thing is hardly considered significant news in the US, though in its size and scope it is surely historically unprecedented. Nor does it seem strange to us that no other country on the planet has more than a tiny number of bases outside its own territory.

The Russians have a scattered few in the former SSRs of the Soviet Union and a single old naval base in Syria that has been in the news of late; the French still have some in Francophone Africa; the British have a few leftovers from their own imperial era, including the island of Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean, which has essentially been transformed into an American base; and the Chinese may be in the process of setting up a couple of modest bases as well.

Add up every non-American base on foreign soil, however, and the total is probably less than two per cent of the American empire of bases.

Investing in war

It would, by the way, be a snap to construct a little quiz like this every couple of weeks from US military news that’s reported but not attended to here, and each quiz would make the same essential point. From Washington’s perspective, the world is primarily a landscape for arming for, garrisoning for, training for, planning for and making war. War is what we invest our time, energy and treasure in on a scale that is, in its own way, remarkable, even if it seldom registers in this country.

| “The US actually tripled its arms sales last year, hitting a record high, and cornering almost 78 per cent of the global arms trade.” |

In a sense (leaving aside the obvious inability of the US military to actually win wars), it may, at this point, be what we do best. After all, whatever the results, it’s an accomplishment to send 200 Marines to Guatemala for a month of drug interdiction work, to get those Global Hawks secretly to Australia to monitor the Pacific, and to corner the market on things that go boom in the night.

Think of it this way: the United States is alone on the planet, not just in its ability, but in its willingness to use military force in drug wars, religious wars, political wars, conflicts of almost any sort, constantly and on a global scale. No other group of powers collectively even comes close. It also stands alone as a purveyor of major weapons systems and so as a generator of war. It is, in a sense, a massive machine for the promotion of war on a global scale.

We have, in other words, what increasingly looks like a monopoly on war. There have, of course, been warrior societies in the past that committed themselves to a mobilised life of war-making above all else. What’s unique about the United States is that it isn’t a warrior society. Quite the opposite.

Washington may be mobilised for permanent war. Special operations forces may be operating in up to 120 countries. Drone bases may be proliferating across the planet. We may be building up forces in the Persian Gulf and “pivoting” to Asia.

Warrior corporations and rent-a-gun mercenary outfits have mobilised on the country’s disparate battlefronts to profit from the increasingly privatised 21st-century American version of war. The American people, however, are demobilised and detached from the wars, interventions, operations and other military activities done in their name.

As a result, 200 Marines in Guatemala, almost 78 per cent of global weapons sales, drones flying surveillance from Australia – no one here notices; no one here cares.

War: it’s what we do the most and attend to the least. It’s a nasty combination.

Perhaps the most anticipated speech at this year’s UN General Assembly meeting will be that of Egypt’s new president, Mohammed Morsi. The annual heads-of-state palooza at Turtle Bay is generally a yawner where very little news is made. The Turkish delegation’s brawl with UN security was the only memorable moment last year. In the past, Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmedinejad and Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez could always be counted on for some shock value, but they have grown tedious. The flap about where Muammar Qadhafi would pitch his tent in 2009 was fun, but only in a sort of grotesque way—that was the rehabilitated Qadhafi who was morphed into an “eccentric desert leader” rather than the ruthless dictator he really was.

This year should be far more interesting with five new leaders (Libya, Somalia, Tunisia, Yemen, and Egypt) in attendance, especially with Morsi who made quite an impression at the meeting of the Non-Aligned Movement in Tehran in August. Indeed, Morsi has a reputation for being a straight shooter who is unlikely to be intimidated by his surroundings. When he sat in the People’s Assembly between 2000 and 2005, Morsi led a group of seventeen so-called independent Muslim Brothers, an organization from which Morsi resigned after being elected president, though his continuing ties to it are indisputable. During that time he and his fellow parliamentarians from the Brotherhood sought to hold the government and the then ruling-National Democratic Party accountable for various sins. He has, according to my friend Tarek Masoud of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, a “fighting spirit,” a character trait that came through in the very good interview that David Kirkpatrick and Steven Erlanger of the New York Times conducted with the new Egyptian president on the eve of his trip to New York.

When it is Morsi’s turn at the podium in the General Assembly on Wednesday, he is likely to run through a litany of issues that are fairly standard for Egyptian foreign policy—the Nile waters and Africa, Nuclear Weapons Free Zone in the Middle East, regional stability, and Arab and Muslim solidarity, especially after the uproar of the film Innocence of Muslims. He’ll also likely spend some extra time paying homage to the martyrs of the Egyptian uprising, which is part of the Brotherhood’s effort to create a narrative that fuses the group with January 25th even though as an organization, the Brothers were a little late to Tahrir Square. Morsi will also likely repeat his call for Bashar al Assad to step down. Calling Assad out at the world forum has three benefits for the Egyptian president. In addition to being the morally right thing to do, it places the Brothers and him on the side of revolutionary movements in the Arab world and demonstrates that Egypt intends to be a regional player once again.

It is also likely—given the signals emerging from the Kirkpatrick-Erlanger interview—that Morsi will take a strong stand on the Palestinian issue. This is nothing new for the Egyptians, but Morsi (and the Brotherhood) has credibility on this issue. True, the border between Gaza and Sinai remains tightly controlled and by all accounts the Egyptian and Israeli militaries continue to cooperate, but the Brothers have a long and principled history of opposing Zionism, Camp David, the Egypt-Israel peace treaty, and normalization of relations between Cairo and Jerusalem. Morsi is clearly interested in demonstrating that it is a new era in Egypt-Israel relations, where the Egyptian government will hold the Israelis accountable for developments in the West Bank and Gaza Strip as well as the ongoing standstill in negotiations between Israel and the Palestinian Authority.

In an important twist, Morsi may well serve notice to the United States that he is turning over the trilateral logic of U.S.-Egypt relations in which Washington has tended to evaluate its ties with Egypt through Cairo’s ties with Jerusalem. Morsi seems intent on changing this state of affairs and his speech to the UN provides a good opportunity to alter the prevailing dynamics of U.S.-Egypt relations, telling the world body—perhaps not in so many words—that the quality of Egypt’s relationship with the United States will hereafter be based in part on Washington’s willingness to work toward a solution to the Palestinian problem, which means leaning on Jerusalem. Given the asymmetry of power between Egypt and the United States, it is unclear how Cairo could hold Washington responsible for the Palestinian-Israeli conflict in this way, particularly taking into account Israel’s popularity among the American public and the political strength of pro-Israel groups. Still, if Morsi does take a strong rhetorical stand on a relationship that is widely believed to have benefited Israel at the expense of Egypt and Arab causes like the Palestinians, it is sure to play extremely well at home, which is what UN General Assembly speeches are all about anyway.

A provocative ad which debuted last month in San Francisco is making its way to New York subways today.

Starting from Monday, September 24, 2012, as the UN General Assembly picks up momentum in New York and heads of states from around the world come to the Big Apple for their annual gatherings, New Yorkers and their out of town guests are treated to quite an advertising spectacle.

“In any war between the civilised man and the savage,” the ad will read, “support the civilised man. Support Israel. Defeat Jihad.”

The ad began its debut last month in San Francisco on city buses, and is now heading to New York subways.According to CNN: “New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority initially rejected the ad… But the authority’s decision was overturned last month when a federal judge ruled that the ad is protected speech under the First Amendment.”

An organisation called the “American Freedom Defence Initiative” has produced the ad and “has been fighting to place the message in New York’s subway system since last year after the authority refused to display it”.

According to the Washington Post, “A conservative blogger who once headed a campaign against an Islamic centre near the September 11 terror attack site won a court order to post the ad in 10 subway stations next Monday… The blogger, Pamela Geller, said she filed suit Thursday in the nation’s capital to post the ad in Washington’s transit system after officials declined to put up the ad in light of the uproar in the Middle East over the anti-Islam film.”

Over the last few days, since the news of this ad started circulating the media, pictures of the ad have appeared on the internet – with many Americans categorically denouncing its evident racism, while the more enterprising New Yorkers initiated a Twitter campaign to protest the ad to start on the same Monday with the hashtag #MySubwayAd.

What’s in an ad?

Two crucial aspects of this ad have far reaching implications that its immediate and boorish racism can in fact conceal. We need to unpack this ad for the sign of something else that it is – first, who exactly is its audience, and second, what to make of its vintage vulgarity.

“We need to unpack this ad for the sign of something else that it is – first, who exactly is its audience, and second, what to make of its vintage vulgarity.”

The timing of it with the UN General Assembly may create the impression that it is intended for a primarily global audience, while its astonishing vulgarity might make it appear as exceptional and the work of a lunatic fringe. Both these impressions need further scrutiny.

Though the timing may in fact have targeted a global impact, a proposition compromised by the fact that the UN delegates don’t usually take the bus or the subway in New York and are in fact chauffeured around in their diplomatic limousines while escorted by the New York police motorcades, the primary target of the ad is in factdomestic and only by extension global. That it is intended for Washington, DC may also mean targeting foreign embassies, but coupled by its initial campaign in San Francisco almost definitively marks its domestic targets. Targeting the domestic and foreign audiences need not be mutually exclusive, and can in fact be complementary. But given the foreign policy implications of the ad, the domestic audience should not be overlooked.

Domestic targets

The fact that this ad is primarily (but not exclusively) targeted for domestic use is evident in the two dominant tropes of “civilised man” and “savage” – the two terms immediately applied by the white supremacist European colonial settlers in the US and the Native Americans, respectively. As I have said on many occasions, the visual tropes and active vocabularies of white supremacist racism is very limited and they keep regurgitating it against one target of their anxiety or another. The “civilised man” was (and remains) the white European man and “the savage” was his designated trope for the Native Americans. “Savage” has in the course of American history been subsequently extended and transmuted to include African Americans, Latino Americans, and now only by extension Muslim Americans – all the moving targets of anxiety for white supremacists.

Like all racist adages, the ad partakes in very old racist tropes and the appearance of the phrase “civilised man” twice in the span of a short sentence reveals the racist pedigree back to the early American history – and that it is in fact a woman who is using this phrase is an absolutely delightful mot juste that reveals the supreme victory of the phrase in the collective consciousness of racist brutes beyond age and gender!

The target of the ad is thus primarily domestic against what is called multiculturalism, old and new immigrants, and the massive demographic changes in American society – a deeply anxiety-provoking fact for the fictive white man and his white supremacist limited regime of knowledge at work here.

Precisely the same anxiety had led only a decade ago to “the clash of civilisation” thesis by Samuel Huntington, which Gellar now violently vulgarises. In my critique of “the clash of civilisation” thesis, published more than a decade ago in the International Journal of Sociology, I have already demonstrated in detail how the rise of civilisational thinking during the 1990s in the US was already targeted far more domestically than globally – a claim I made in 2001 and confirmed four years later when Samuel Huntington published his Who Are We?: The Challenges to America’s National Identity (2005).

The “clash of civilisation” thesis was the Harvard University professoriate version of this illiterate buffoonery that is now riding on New York subways – identical racism put in two different parlance, one polished and careful and the other vulgar and naked, both targeting domestic non-white Native Americans, African Americans, and recent immigrants by way of consolidating a fictive white man at the centre of American history and political culture.

The fact that the principal culprit behind this bigotry is in fact a domestic danger to reason and sanity in the US has not been lost on progressive Americans who have been on her case for quite some time. The Southern Poverty Law Centre, a non-profit civil rights organisation “dedicated to fighting hate and bigotry, and to seeking justice for the most vulnerable members of society”, has in fact done a thorough exposé on her.

In a way, this ad is in fact a badge of honour for Muslims to have joined the ranks of Native Americans, African Americans, Latino Americans and others who have periodically been the subject of white supremacist hatred. Muslims have finally arrived in America!

“The ad is not an exception that proves a rule, but an exception that camouflages the rule.”

In this sense, Geller’s pathological utterance in public is thus identical toMitt Romney’s now infamous tape in which he openly denigrates and dismisses half of the American population as lazy freeloaders. Romney and Gellar are just not too intelligent to say what they mean in more guarded language. Indeed as Romney subsequently said in an attempt to justify his 47 per cent comment, he did not put it elegantly. Exactly. He is a badly educated and vulgar rich man who says things very nakedly, as is Geller. Two vulgar racist class-conscious supremacists thrown into the public ill-prepared to camouflage their racism as a Harvard professor would.

The exception that hides the rule

The second most visible aspect of this ad, immediately connected to the first, is its astonishing vulgarity. That vulgarity in effect and unwillingly mimics Zionism – stealing other people’s homeland and crying uncle! By incitement to murder, by encouraging ethnic cleansing, by being associated with a vulgar Zionist who has been an inspiration to the European mass murderer, Anders Breivik, this ad stages a particular brand of American Zionism appropriately placed where usually advertisements for Calvin Klein underwear or “Gentlemen’s clubs” and other similar commercials appear.

By thus commercialising the Zionist cause, it places it squarely within the visual regime of loutish consumerism – where it now squarely belongs. It thrives on mimicking Zionism in its advanced stage of having wedded the ethnic cleansing of Palestine to the consumerist fetishism definitive to American militarism.

But Americans and non-Americans alike baffled by the depth of this vulgarity in effect blind themselves to what this blatant vulgarity conceals and reveals at one and the same time.

To understand this concealment, this commodified mystification of Zionism, we need a quick detour to the sublime insight of the exquisite French semiotician Roland Barth (1915-1980) in his reading of Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront(1954). In one of his most insightful short essays in his Mythologies (1957), “A Sympathetic Worker”, Barth speaks of a certain kind of “truth vaccine” by which he means how in Elia Kazan’s film “a small gang of mobsters is made to symbolise the entire body of employers, and once this minor disorder is acknowledged and dealt with like a trivial and disgraceful pustule, the real problem is evaded, is never even named, and is thereby exorcised”.

This is exactly what we are seeing here. The thick vulgarity of the ad turns it into a caricature, safely distances it from Harvard political scientists theorising “the clash of civilisation”, as it distances it from the very core of American imperialism, so that “once this minor disorder is thus identified and acknowledged” as “a trivial and disgraceful pustule”, the real problem – namely the fact that the entire American foreign policy, its demonisation of Muslims in the courses it teaches in its military academies, its flushing the Quran down the toilet by way of torturing Muslim “savages”, by drone attacks on innocent people in Pakistan or Afghanistan, and by its unconditional support for Israel repeatedly articulated by President Obama are all “evaded, never even named, and thereby exorcised”.

So if you are angered, disgusted and outraged by this ad, watch it, you are being taken for a ride, and not just on San Francisco buses or the New York subway cars. For the ad is not an exception that proves a rule, but an exception that camouflages the rule.

As to what exactly should be the Muslim response to this racist Islamophobic ad – well you just read one response: no kicking, no screaming, no climbing any walls, no burning any flag, no act of violence, no room for any corrupt Pakistani politician to cover up his own corruption by inciting to murder – just a little theoretical tit for a bit of vulgar tat. They want to terrorise you into silence; you turn around and theorise their vulgarity. That’s all – on to the next atrocity.

Hamid Dabashi is the Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University in New York. His most recent book is The Arab Spring: The End of Postcolonialism (Zed 2012).